Ramblin’ On: The Birth, Life And Rebirth Of Southern Rock

From original pioneers Elvis and Little Richard, to the Allmans and Cadillac Three, Southern rock has made a global impact far beyond its original boundaries. But then again… maybe it had no boundaries to begin with?

If you find the birth certificate for rock’n’roll, you won’t see Dartford written on it. Nor Liverpool. Not even Pennsylvania, where the pioneering Bill Haley grew up. No sir… Rock’n’roll is from the Southern states of the US of A. And whenever it wants to go back to its roots, it pays homage to the sounds that were created down there. Rock is Southern at heart. And Southern rock, for many fans, musicians and critics, represents the most authentic rock’n’roll of all.

Let’s go back to the King. Elvis Presley shot straight out of Memphis, a hip-shakin’, rockabillyin’, parent-scarin’ fireball who took Southern sounds to the world. Elvis’ early records had all the hallmarks of Southern rock. They were cut when the feeling hit, rather than being premeditated, planned productions. They were full of emotion. Above all else, they blended blues and country, black and white. The music rocked like the blues, but half of it was hillbilly: hence rockabilly.

Let’s go back to the King. Elvis Presley shot straight out of Memphis, a hip-shakin’, rockabillyin’, parent-scarin’ fireball who took Southern sounds to the world. Elvis’ early records had all the hallmarks of Southern rock. They were cut when the feeling hit, rather than being premeditated, planned productions. They were full of emotion. Above all else, they blended blues and country, black and white. The music rocked like the blues, but half of it was hillbilly: hence rockabilly.

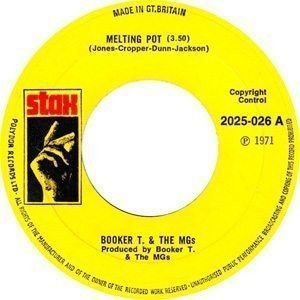

This mixture should not be a surprise: the South may have been racially segregated, but the airwaves were free: white folk could enjoy rhythm and blues on the radio. African-Americans could hear country and pop. Elvis was recording for Sun, a Memphis studio and label that also specialised in blues and country, a place where both Howlin’ Wolf and Johnny Cash could work and deliver great records with no sense of contradiction. It was Booker T & The MGs, another Memphis act, who would record ‘Melting Pot’ – a term that easily applies to the city’s music. There were no borders: if it worked, it would be part of the mix. Elvis loved the blues; Howlin’ Wolf made no secret of the influence that country singer Jimmie Rodgers’ blue yodel had on his remarkable vocal style.

Wolf’s early 50s recordings at Sun were largely acoustic affairs. Licensed to RPM and Chess, it was the latter who would land the Wolf’s contract permanently, and his move north to Chicago marked the point where his records became almost entirely electric. If Wolf, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and others had not moved to Chicago, rock’n’roll might have taken a very different path. Competing with city noise, appearing in bigger bars where the crowds were rowdier, the blues had to become amplified (though Wolf played an electric guitar long before he headed to Chicago). The attitude was still Southern, but the blues rocked harder and louder. In the South, Wolf and Muddy, recording for local, badly distributed labels, might have been ignored. Signed to Chess, their music reverberated around the world for decades. Great googa mooga, the South was getting heard.

Wolf’s early 50s recordings at Sun were largely acoustic affairs. Licensed to RPM and Chess, it was the latter who would land the Wolf’s contract permanently, and his move north to Chicago marked the point where his records became almost entirely electric. If Wolf, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and others had not moved to Chicago, rock’n’roll might have taken a very different path. Competing with city noise, appearing in bigger bars where the crowds were rowdier, the blues had to become amplified (though Wolf played an electric guitar long before he headed to Chicago). The attitude was still Southern, but the blues rocked harder and louder. In the South, Wolf and Muddy, recording for local, badly distributed labels, might have been ignored. Signed to Chess, their music reverberated around the world for decades. Great googa mooga, the South was getting heard.

The blues had a baby and they called it rock’n’roll, as the song claims. It was a difficult birth. Rock’n’roll outraged polite society. It was all very well for black folk to be listening to rhythm and blues, but when white folk began doing it… record-smashing was an occasional (but well-publicised) event in the South, where the music’s opponents could attract publicity for their claims that rock’n’roll was ungodly. The Reverend Jimmie Snow delivered sermons about the “evil” of the music in Nashville (note the location). Jimmie was the son of Canadian country singer Hank Snow, so maybe he had more reason than most to fear a white audience adopting this exciting new music, but this preacher was not alone. The Alabama White Citizens Council condemned rock’s vulgarity as a “means for the white man to be driven to the level of the…” and then used a word so taboo, it cannot be typed here. This music, a product of all that was wonderful about Southern culture, was condemned in its heartland. But there was no stopping it.

Southern rockers were crucial to the propagation of teenage music: until they came along, the kids only had the same pleasures their parents pursued. Elvis was joined by Jerry Lee Lewis, the wildest of Sun’s rockers, rock’n’roll’s equivalent of a hellfire preacher and the Southern rock legacy incarnate: hillbilly, country, rhythm’n’blues, gospel; he knew it all and could deliver it within a dynamite live act. There was Carl Perkins, a great guitar picker and songwriter who would have flourished on either side of the country/blues divide in different circumstances. There was also Johnny Cash, who brought a certain rebellion to country, and added a spot of mariachi brass. In New Orleans, Fats Domino and Dave Bartholomew took real rhythm and blues to a white audience, a rollicking, rolling sound with plenty of humour straight out of the juke joints. From Macon, Georgia, came the most outrageous piano-playin’, pompadour-shakin’ devil to make it in the mid-50s: Little Richard. He was a flat-out lewd rocker, untamed, wild and curiously camp, yet both boys and girls loved him. Richard felt the contradiction of his calling more strongly than most and renounced rock’n’roll for gospel several times in his long career. Northern city folk could party non-stop if they liked, but the Southern rocker was brought up to fear God, and this too fed into the music. There is frequently a repentant tone in Southern sounds: even ‘Free Bird’, one of the South’s rock anthems, carries a hint of remorse.

Southern rockers were crucial to the propagation of teenage music: until they came along, the kids only had the same pleasures their parents pursued. Elvis was joined by Jerry Lee Lewis, the wildest of Sun’s rockers, rock’n’roll’s equivalent of a hellfire preacher and the Southern rock legacy incarnate: hillbilly, country, rhythm’n’blues, gospel; he knew it all and could deliver it within a dynamite live act. There was Carl Perkins, a great guitar picker and songwriter who would have flourished on either side of the country/blues divide in different circumstances. There was also Johnny Cash, who brought a certain rebellion to country, and added a spot of mariachi brass. In New Orleans, Fats Domino and Dave Bartholomew took real rhythm and blues to a white audience, a rollicking, rolling sound with plenty of humour straight out of the juke joints. From Macon, Georgia, came the most outrageous piano-playin’, pompadour-shakin’ devil to make it in the mid-50s: Little Richard. He was a flat-out lewd rocker, untamed, wild and curiously camp, yet both boys and girls loved him. Richard felt the contradiction of his calling more strongly than most and renounced rock’n’roll for gospel several times in his long career. Northern city folk could party non-stop if they liked, but the Southern rocker was brought up to fear God, and this too fed into the music. There is frequently a repentant tone in Southern sounds: even ‘Free Bird’, one of the South’s rock anthems, carries a hint of remorse.

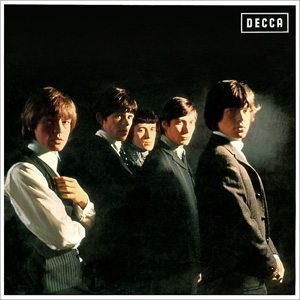

The world was listening, and the fledgling British rock’n’roll copied. Lonnie Donegan, who named himself after New Orleans bluesman Lonnie Johnson, started the skiffle boom by adding a beat to folk-blues songs and turned tunes by Louisiana legend Lead Belly, such as ‘Diggin’ My Potatoes’ and ‘Rock Island Line’, into hits. When it came to the best of early British rock, most musicians aimed for the Sun sound; even showbiz rocker Tommy Steele started out seeking a Memphis-styled feel; five years on, Billy Fury’s The Sound Of Fury LP was arguably the most authentic rockabilly made outside the US. Though The Beatles created a less derivative form of Brit rock, largely flushing away their predecessors, they still included a song by Alabama country-soul singer Arthur Alexander on Please Please Me, their debut album. But the line of British Southern rock was more strongly represented by a band that arrived in The Beatles’ wake, creating a dirtier, wilder form of the music: The Rolling Stones.

The Stones’ first album was jammed with rocked-up blues tunes written by singers from below the Mason-Dixon line. Willie Dixon’s ‘I Just Want To Make Love To You’, Jimmy Reed’s ‘Honest I Do’, Bo Diddley’s ‘I Need You Baby’, Slim Harpo’s ‘I’m A King Bee’, Ted Jarrett’s ‘You Can Make It If You Try’, and Rufus Thomas’ ‘Walking The Dog’; this was fundamentally a Southern rock album, though from the South of England, rather than the US. Further British R&B bands quickly followed: The Yardbirds, Small Faces, Pretty Things, Them… it may not have been rock as the Southern states knew it, but it was built on the same foundations. The curious thing is, the more assertively individual the Stones became as the 60s went on, the more Southern they grew.

The Stones’ first album was jammed with rocked-up blues tunes written by singers from below the Mason-Dixon line. Willie Dixon’s ‘I Just Want To Make Love To You’, Jimmy Reed’s ‘Honest I Do’, Bo Diddley’s ‘I Need You Baby’, Slim Harpo’s ‘I’m A King Bee’, Ted Jarrett’s ‘You Can Make It If You Try’, and Rufus Thomas’ ‘Walking The Dog’; this was fundamentally a Southern rock album, though from the South of England, rather than the US. Further British R&B bands quickly followed: The Yardbirds, Small Faces, Pretty Things, Them… it may not have been rock as the Southern states knew it, but it was built on the same foundations. The curious thing is, the more assertively individual the Stones became as the 60s went on, the more Southern they grew.

While American pop ostensibly spent the period between 1964-66 catching up with the music the British Invasion brought to its shores behind The Beatles, it had some startlingly original sounds of its own being made in the South, though nobody thought of it as a movement at the time. The best of it came out of the Lone Star state.

Texas had made a huge impact on early rock’n’roll. Roy Orbison had cut records for Sun in the 50s, and his big beat ballads for the Monument label in the first half of the 60s suggested desperate nights in small Southern towns, a man battling a huge emotional landscape, like a frontiersman trying to survive a trek across the Big Bend. Lubbock, Texas, outfit Buddy Holly & The Crickets brought self-sufficiency and innovation to rock. Holly was such a great songwriter that he could have survived in any genre, and his inventiveness in the studio was remarkable. He’d do things like have drummer Jerry Allison playing his knees for a special slapping sound on ‘Everyday’, a record that also featured a celeste, a tinkling keyboard instrument that made its debut in rock’n’roll in 1957, when Holly cut the record in the unlikely musical hotbed that was Clovis, New Mexico. The idea of bands writing their own material was not an invention of The Beatles, as is commonly thought; doubtless Paul McCartney acknowledged this by snapping up Holly’s publishing catalogue for his own company, MPL. In his short lifetime, Holly created a songbook that had a wide-ranging influence on rock, from the Stones covering ‘Not Fade Away’ (the long-suffering Allison had played a cardboard box on the original) to ‘That’ll Be The Day’ providing the seeds for David Essex’s entire career when it gave its name to the movie that provided his breakthrough.

Texas had made a huge impact on early rock’n’roll. Roy Orbison had cut records for Sun in the 50s, and his big beat ballads for the Monument label in the first half of the 60s suggested desperate nights in small Southern towns, a man battling a huge emotional landscape, like a frontiersman trying to survive a trek across the Big Bend. Lubbock, Texas, outfit Buddy Holly & The Crickets brought self-sufficiency and innovation to rock. Holly was such a great songwriter that he could have survived in any genre, and his inventiveness in the studio was remarkable. He’d do things like have drummer Jerry Allison playing his knees for a special slapping sound on ‘Everyday’, a record that also featured a celeste, a tinkling keyboard instrument that made its debut in rock’n’roll in 1957, when Holly cut the record in the unlikely musical hotbed that was Clovis, New Mexico. The idea of bands writing their own material was not an invention of The Beatles, as is commonly thought; doubtless Paul McCartney acknowledged this by snapping up Holly’s publishing catalogue for his own company, MPL. In his short lifetime, Holly created a songbook that had a wide-ranging influence on rock, from the Stones covering ‘Not Fade Away’ (the long-suffering Allison had played a cardboard box on the original) to ‘That’ll Be The Day’ providing the seeds for David Essex’s entire career when it gave its name to the movie that provided his breakthrough.

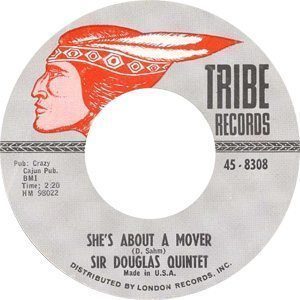

When the mid-60s arrived, Texas was ready with some of America’s most exciting ripostes to the Fabs’ dominance. Sam The Sham & The Pharaohs hit in the summer of 1965 with ‛Wooly Bully’, a record so ragged and raw that some critics have claimed it as the first flowering of garage punk. It was the biggest hit of the year, according to its performance on the Billboard charts, but never quite made it to No.1. Sam, born in Dallas and of Mexican-American heritage, followed up with several huge hits, including another No.2, ‘Li’l Red Riding Hood’. Texas knew how to party, and further proof came with another great ’65 hit in a different style, Sir Douglas Quintet’s ‘She’s About A Mover’. Riding on a brutally blunt guitar part and poky Vox organ stabs, the record somehow managed to be pop, R&B and Tex-Mex all at once. The band would go on to enjoy several hits, including 1969’s ‘Mendocino’, which may have been named after a place in California, but was pure Southern rock.

When the mid-60s arrived, Texas was ready with some of America’s most exciting ripostes to the Fabs’ dominance. Sam The Sham & The Pharaohs hit in the summer of 1965 with ‛Wooly Bully’, a record so ragged and raw that some critics have claimed it as the first flowering of garage punk. It was the biggest hit of the year, according to its performance on the Billboard charts, but never quite made it to No.1. Sam, born in Dallas and of Mexican-American heritage, followed up with several huge hits, including another No.2, ‘Li’l Red Riding Hood’. Texas knew how to party, and further proof came with another great ’65 hit in a different style, Sir Douglas Quintet’s ‘She’s About A Mover’. Riding on a brutally blunt guitar part and poky Vox organ stabs, the record somehow managed to be pop, R&B and Tex-Mex all at once. The band would go on to enjoy several hits, including 1969’s ‘Mendocino’, which may have been named after a place in California, but was pure Southern rock.

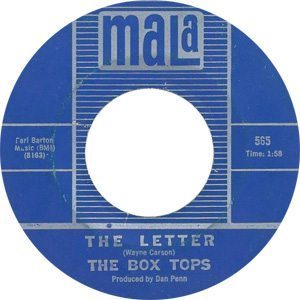

Memphis, Tennessee, had always been associated with the blues: its Beale Street is a centre for the music and is considered the spiritual home for the likes of BB King, Bobby Bland and Junior Parker. The blues fed R&B, and R&B fed soul with an added dose of gospel. Southern soul fed the British mod movement, with Memphis DJ-singer Rufus Thomas just one of many who found his songs covered by suit-wearing mods in the UK. Thomas recorded for Memphis label Stax, which mixed white and black musicians as if there was no difference – which in this case, there wasn’t. Its house rhythm section, Booker T & The MGs, consisted of two black musicians and two white ones, each as funky as the next. Stax’s recording suite had a rival across town which also mixed African-American sounds and rock’n’roll with ease: American Sound Studio. In 1967, the year it opened, it scored a worldwide hit with ‘The Letter’, a record which mixed soul and psychedelic pop in equal measure, sung by a local band, The Box Tops. Their records were for the most part written and produced by American Studio staffers Chips Moman, Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham, Southern boys who performed a similar function for Elvis Presley (‘Suspicious Minds’), Dusty Springfield (‘Son Of A Preacher Man’) and numerous others. This blend of soul, country and rock’n’roll was fundamental to the development of Southern rock.

Memphis, Tennessee, had always been associated with the blues: its Beale Street is a centre for the music and is considered the spiritual home for the likes of BB King, Bobby Bland and Junior Parker. The blues fed R&B, and R&B fed soul with an added dose of gospel. Southern soul fed the British mod movement, with Memphis DJ-singer Rufus Thomas just one of many who found his songs covered by suit-wearing mods in the UK. Thomas recorded for Memphis label Stax, which mixed white and black musicians as if there was no difference – which in this case, there wasn’t. Its house rhythm section, Booker T & The MGs, consisted of two black musicians and two white ones, each as funky as the next. Stax’s recording suite had a rival across town which also mixed African-American sounds and rock’n’roll with ease: American Sound Studio. In 1967, the year it opened, it scored a worldwide hit with ‘The Letter’, a record which mixed soul and psychedelic pop in equal measure, sung by a local band, The Box Tops. Their records were for the most part written and produced by American Studio staffers Chips Moman, Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham, Southern boys who performed a similar function for Elvis Presley (‘Suspicious Minds’), Dusty Springfield (‘Son Of A Preacher Man’) and numerous others. This blend of soul, country and rock’n’roll was fundamental to the development of Southern rock.

The threesome had also worked at Rick Hall’s FAME studio at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where they cut the majority of Aretha Franklin’s smash hit ‘Do Right Woman, Do Right Man’. Another regular in the studio was a 22-year-old guitarist with a nice line in slide licks: Duane Allman. He was hired at the end of 1968 and played on gems by Herbie Mann, Percy Sledge, Delaney & Bonnie, Aretha, Laura Nyro and the great soul saxophonist King Curtis. But it was the first session Allman laid for Hall that changed the course of his career – and Southern rock. Wilson Pickett’s version of ‘Hey Jude’ was hardly subtle, because Pickett didn’t do subtle. But Allman’s guitar solo at the end caught the ears of both Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, who hired him to work on the bulk of the above-mentioned records, and another guy who was no mean guitar-slinger himself: Eric Clapton.

The threesome had also worked at Rick Hall’s FAME studio at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where they cut the majority of Aretha Franklin’s smash hit ‘Do Right Woman, Do Right Man’. Another regular in the studio was a 22-year-old guitarist with a nice line in slide licks: Duane Allman. He was hired at the end of 1968 and played on gems by Herbie Mann, Percy Sledge, Delaney & Bonnie, Aretha, Laura Nyro and the great soul saxophonist King Curtis. But it was the first session Allman laid for Hall that changed the course of his career – and Southern rock. Wilson Pickett’s version of ‘Hey Jude’ was hardly subtle, because Pickett didn’t do subtle. But Allman’s guitar solo at the end caught the ears of both Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, who hired him to work on the bulk of the above-mentioned records, and another guy who was no mean guitar-slinger himself: Eric Clapton.

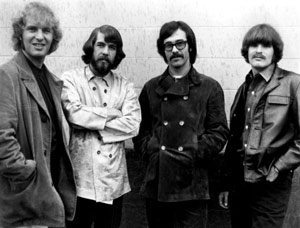

Duane formed The Allman Brothers Band in 1969, alongside his brother Gregg (keyboards), Dickey Betts (vocals and guitar), Butch Trucks and Jaimoe Johanson (drums) and Berry Oakley (bass). While the band was a disaster area in terms of excess and premature deaths (Duane Allman and Oakley both died in the early 70s), its all-too-brief original incarnation made a mark on music that nigh-on epitomised Southern rock. The band’s first couple of albums received great notices, and the third, At Fillmore East, proved too strong for the public to ignore. It mixed blues classics – Blind Wille McTell’s ‘Statesboro’ Blues’, T-Bone Walker’s ‘Stormy Monday’, Elmore James’ ‘Done Somebody Wrong’ – with the band’s own compositions, which suddenly took on a new status. ‘Whipping Post’ and ‘In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed’, plus their tribute to a key Southern metropolis, ‘Hot ’Lanta’ (ie, Atlanta) – every one was a gem. The band brought any influence into their work, like a one-stop shop for the roots of US music. ‘Elizabeth Reed’ was jazzy; the blues and R&B were covered; they rocked like a ship in a storm when they wanted; and there was a touch of country, delivered by Duane’s heartfelt slide lines. The Allmans had made it.

Duane formed The Allman Brothers Band in 1969, alongside his brother Gregg (keyboards), Dickey Betts (vocals and guitar), Butch Trucks and Jaimoe Johanson (drums) and Berry Oakley (bass). While the band was a disaster area in terms of excess and premature deaths (Duane Allman and Oakley both died in the early 70s), its all-too-brief original incarnation made a mark on music that nigh-on epitomised Southern rock. The band’s first couple of albums received great notices, and the third, At Fillmore East, proved too strong for the public to ignore. It mixed blues classics – Blind Wille McTell’s ‘Statesboro’ Blues’, T-Bone Walker’s ‘Stormy Monday’, Elmore James’ ‘Done Somebody Wrong’ – with the band’s own compositions, which suddenly took on a new status. ‘Whipping Post’ and ‘In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed’, plus their tribute to a key Southern metropolis, ‘Hot ’Lanta’ (ie, Atlanta) – every one was a gem. The band brought any influence into their work, like a one-stop shop for the roots of US music. ‘Elizabeth Reed’ was jazzy; the blues and R&B were covered; they rocked like a ship in a storm when they wanted; and there was a touch of country, delivered by Duane’s heartfelt slide lines. The Allmans had made it.

However, Duane had already tasted success. British axeman Eric Clapton had sought him out at a Brothers’ gig in Miami, where the ex-Cream star was recording an album. Duane asked if he could come to the studio to watch, but pretty soon the two guitar stars were jamming together and Duane played on 11 tracks on Derek & The Dominos’ Layla And Other Love Songs. While Clapton was not a Southerner, the music bore the hallmarks of the genre. The title track was a massive hit, and Allman’s slide on its lengthy, slower second section was a masterclass in wringing heartbreaking emotion from wires across a plank of wood. Clapton wanted Allman in his group full-time, but the Brother had his own band to break. The two guitarists would never record together again: Duane died in October ’71 from injuries sustained in a motorbike crash. The Allmans continued to record fine music, however, dedicating their Eat A Peach album to their fallen leader.

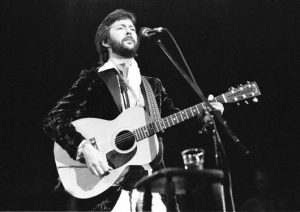

Clapton’s music had been on a Southern rock path for years. Blind Faith, the supergroup he’d formed with Steve Winwood of Traffic, Rik Grech of Family and Ginger Baker, the drummer who’d played alongside him in Cream, showed elements of the style of music to be found on Layla – particularly Clapton’s own ‘Presence Of The Lord’ and Winwood’s ‘Can’t Find My Way Home’. Clapton had also worked with Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, a session that would ensure that the Derek & The Dominos band would gel: every member had played with Delaney & Bonnie at some point. In many respects, Clapton has been a Southern rocker ever since.

Clapton’s music had been on a Southern rock path for years. Blind Faith, the supergroup he’d formed with Steve Winwood of Traffic, Rik Grech of Family and Ginger Baker, the drummer who’d played alongside him in Cream, showed elements of the style of music to be found on Layla – particularly Clapton’s own ‘Presence Of The Lord’ and Winwood’s ‘Can’t Find My Way Home’. Clapton had also worked with Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, a session that would ensure that the Derek & The Dominos band would gel: every member had played with Delaney & Bonnie at some point. In many respects, Clapton has been a Southern rocker ever since.

His journey South was not unique. The Rolling Stones emerged from their late 60s psychedelic phase to become Southern rockers par excellence. Keith Richards had fallen under the influence of Gram Parsons, a former member of The Byrds and pioneer of country-rock. The pair met in 1968: Richards absorbed the nuances of country through Parsons and added them to his own lust for blues and soul. When the band went to Muscle Shoals to cut tracks that would eventually become Sticky Fingers, the die was cast. ‘Brown Sugar’, ‘Wild Horses and ‘Bitch’ all bore the stamp of the South, a style the Stones had already proved they could sell with the 1969 single ‘Honky Tonk Women’ and the Let It Bleed LP, which was packed with Southern talent, including Leon Russell, Bobby Keys, and Merry Clayton, the prominent female voice on ‘Gimme Shelter’.

Another major band of the period came from California, but was effectively playing Southern swamp rock: Creedence Clearwater Revival. Their deceptively simple songs about blue-collar problems and paddle steamers made them as popular with good ol’ boys as they were with hippie heads. And special mention should go to two Brits who took metaphorical coals to Newcastle: Joe Cocker (‘Delta Lady’, ‘Feelin’ Alright’, etc) and Elton John. They both effectively sold the States something Southern it already had.

Another major band of the period came from California, but was effectively playing Southern swamp rock: Creedence Clearwater Revival. Their deceptively simple songs about blue-collar problems and paddle steamers made them as popular with good ol’ boys as they were with hippie heads. And special mention should go to two Brits who took metaphorical coals to Newcastle: Joe Cocker (‘Delta Lady’, ‘Feelin’ Alright’, etc) and Elton John. They both effectively sold the States something Southern it already had.

The Allman Brothers had been signed to Capricorn, a Macon, Georgia, company which specialised in Southern rock. While the Allmans were the label’s flagship act, it had a powerful roster of other Southern stars, such as The Marshall Tucker Band, South Carolina natives who used flute and sax to create a rich fusion of sounds; Delbert McClinton, who eventually found himself covered by The Blues Brothers; and the soulful Wet Willie, who hit big with the sunny, steady-rollin’ ‘Keep On Smilin’’ in 1974.

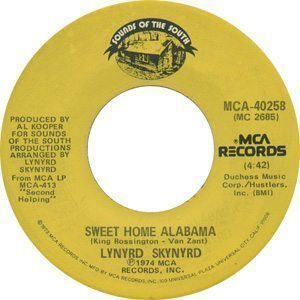

The biggest-selling Southern rock band of the 70s was Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Jacksonville, Florida, act with a happy knack of composing anthems. ‘Free Bird’ (1973) was a building ballad that went Top 20, and the catchy but controversial ‘Sweet Home Alabama’, a riposte to Neil Young’s ‘Southern Man’ and ‘Alabama’, went Top 10 in the US the following year. But, like the Allmans, Skynyrd were a star-crossed band: lead singer Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines and his sister, backing singer Cassie, were all killed in a plane crash, along with three other people, including road manager Dean Kilpatrick. Other members of the band and entourage were seriously injured. In a creepy coincidence, the band had released their fifth album, Street Survivors, just three days earlier. Its sleeve depicted members shrouded in flames. The band continued, but further tragedies chipped away at the original members, including the death of guitarist Allen Collins in a car crash. Other Southern rockers remained cult figures rather than global icons, such as Charlie Daniels, Ozark Mountain Daredevils and Molly Hatchet. Some, such as Black Oak Arkansas, fronted by the ebullient Jim Dandy, were massive in the US but comparatively unappreciated elsewhere.

The biggest-selling Southern rock band of the 70s was Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Jacksonville, Florida, act with a happy knack of composing anthems. ‘Free Bird’ (1973) was a building ballad that went Top 20, and the catchy but controversial ‘Sweet Home Alabama’, a riposte to Neil Young’s ‘Southern Man’ and ‘Alabama’, went Top 10 in the US the following year. But, like the Allmans, Skynyrd were a star-crossed band: lead singer Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines and his sister, backing singer Cassie, were all killed in a plane crash, along with three other people, including road manager Dean Kilpatrick. Other members of the band and entourage were seriously injured. In a creepy coincidence, the band had released their fifth album, Street Survivors, just three days earlier. Its sleeve depicted members shrouded in flames. The band continued, but further tragedies chipped away at the original members, including the death of guitarist Allen Collins in a car crash. Other Southern rockers remained cult figures rather than global icons, such as Charlie Daniels, Ozark Mountain Daredevils and Molly Hatchet. Some, such as Black Oak Arkansas, fronted by the ebullient Jim Dandy, were massive in the US but comparatively unappreciated elsewhere.

The 80s saw the rise of REM, an Athens, Georgia quartet which crossed into the pop mainstream after being championed as an indie outfit. They showed many of the tropes of Southern rock, as did another successful act of the late 80s and early 90s: Crowded House, who were from the very deep south – Australia. If the rockin’ boogie style had become unfashionable following the world dominance of Texas’ ZZ Top, whose 1983 Eliminator delivered three global hits, nobody told Georgia’s Black Crowes, who scored a succession of hit albums in the 90s with a mixture of Stones-influenced hard rock and straight-up Southern sass-in-yo’-ass.

The musical South seems to be a place to find your roots, as Primal Scream, who began as indie kids and passed through rave before settling on a Stones-styled-cum-Muscle Shoals sound, could proudly testify. Southern rock remains a force, even if it’s not vying for singles chart success. The name of Alabama Shakes sounds like an internet dance craze – appropriately so, as the group landed a deal thanks to a huge following online. Their soulful brand of Southern roots rock saw their second album, Sound & Color, shoot straight into the Billboard charts at No.1. Husband-and-wife outfit Tedeschi Trucks Band have built a huge following thanks to the dazzling playing of Derek Trucks, a regular guitarist with the Allmans. The Cadillac Three are an acclaimed act which features a Dobro, a hallmark Southern guitar sound. Poised to release their second album, Bury Me In My Boots, they are signed to Big Machine, a label which has one foot in pop and the other across the border of country and rock. Zac Brown Band, a country outfit with a rock’n’roll dedication to sheer hard graft, are also on its roster, and straight-up rocker Steven Tyler is signed to its Dot imprint. He has now embraced Southen rock, which is some way distant of his work with Aerosmith.

The musical South seems to be a place to find your roots, as Primal Scream, who began as indie kids and passed through rave before settling on a Stones-styled-cum-Muscle Shoals sound, could proudly testify. Southern rock remains a force, even if it’s not vying for singles chart success. The name of Alabama Shakes sounds like an internet dance craze – appropriately so, as the group landed a deal thanks to a huge following online. Their soulful brand of Southern roots rock saw their second album, Sound & Color, shoot straight into the Billboard charts at No.1. Husband-and-wife outfit Tedeschi Trucks Band have built a huge following thanks to the dazzling playing of Derek Trucks, a regular guitarist with the Allmans. The Cadillac Three are an acclaimed act which features a Dobro, a hallmark Southern guitar sound. Poised to release their second album, Bury Me In My Boots, they are signed to Big Machine, a label which has one foot in pop and the other across the border of country and rock. Zac Brown Band, a country outfit with a rock’n’roll dedication to sheer hard graft, are also on its roster, and straight-up rocker Steven Tyler is signed to its Dot imprint. He has now embraced Southen rock, which is some way distant of his work with Aerosmith.

The state of Kentucky has also delivered two major modern Southern rock outfits, the hard-edged Black Stone Cherry, and The Kentucky Headhunters. The latter have one of the most remarkable stories in music, having been around since the late 60s before they finally released a (hit) debut album in 1989. Like Southern rock itself, they just refused to be beat.