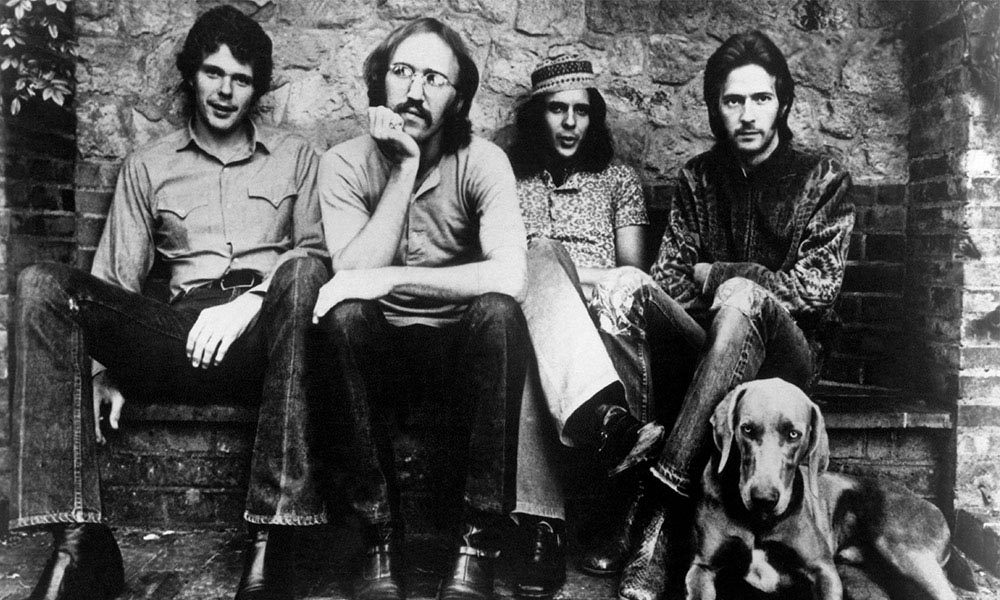

Derek And The Dominos

The arrival of Derek and the Dominos on the British and American music scene in early summer of 1970 and release of the album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs is an epochal event in rock history.

The arrival of Derek and the Dominos on the British and American music scene in early summer of 1970 and the autumnal release of their one and only studio album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs is an epochal event in rock history. Their very existence was one of those happy accidents that in retrospect marked the central point in a momentous era when musicians were discovering The Band, Cream and The Beatles were splitting up and the millionaire supergroup concept was about to take off. Add in major characters of the day like George Harrison, Phil Spector, Delaney & Bonnie Bramlett, the Allman Brothers, Joe Cocker (and The Mad Dogs & Englishmen circus) and you have a thick slice of intrigue.

Eric Clapton, of course, fronted Derek and the Dominos, on the rebound from Blind Faith, and while they weren’t quite as short-lived as that exalted ensemble they were still only really in existence for a year. The legendary song “Layla” wasn’t even a substantial hit on release, neither was the album in the UK but both have grown in stature over the intervening 45 years. The Live In Concert, The Layla Sessions: 20th Anniversary Edition (later upgraded) and Live at the Fillmore flesh out the tale.

For the sake of happenstance, our story begins on August 14. Summer of 1969. Oakland Coliseum. Eric Clapton, Rick Grech, Ginger Baker and Steve Winwood are on stage during the US tour to promote their supergroup Blind Faith. As the English rock lords, two ex-Cream, a Traffic and Family man, lay waste to America’s largest venues it’s known within the ranks that they aren’t enjoying the experience – unlike their support acts, Taste from Ireland, a young group called The Free, and a ramshackle mob of Southern hippies calling themselves Delaney & Bonnie & Friends. Unlike Blind Faith, they are having a fantastic time. Clapton’s good friend George Harrison had recommended them to Clapton, after hearing the duo’s debut album Home, and had even tried to sign them to Apple Records.

Finishing the six week Faith trip in Honolulu, Clapton steals the Bramlett husband and wife team, plus their core band members: drummer Jim Gordon, bassist Carl Dean Radle, pianist Leon Russell, singer Rita Coolidge, the brass of Bobby Keys and Jim Price, and a 20-year old Hammond B3 organist called Bobby Whitlock.

The ragtag bunch of musicians from Illinois, Mississippi, Memphis TN and Tulsa OK begin rehearsals November 1969 for Clapton’s debut solo album (August 1970), also featuring Stephen Stills, which will be recorded in LA and London with Delaney producing a bunch of down-home roots rockers.

Whitlock stuck around the Bramletts to record their fourth album, To Bonnie from Delaney, while their live album, the hastily assembled On Tour With Eric Clapton, hits the American Top 30. Captured at Croydon’s Fairfields Hall this set found Whitlock sharing a stage with Dave Mason and George Harrison and forging a rhythmic bond with Radle and Gordon.

When the majority of the players decide to enlist with Joe Cocker and company, Whitlock finds himself at a loose end. He was tired of hanging out with Delaney and Bonnie in LA and enduring their often-incendiary conflicts. “I’d had enough” Whitlock later recalls, “so I called my friend Steve Cropper and he suggested I get in touch with Eric. Cropper bought my ticket ‘cos I was technically a minor and Eric invited me to England on the spot. I was the first American to stay at Hurtwood.”

In Clapton’s Italianate villa with its views of rolling Surrey countryside the two men cemented a friendship and began writing together. “Just the two of us in this big ole house plus Eric’s assistant, the lady housekeeper, her husband the gardener, and Eric’s dawg Jeep”

Decked out by his aristocratic gipsy pals, stuffed with fabulous antiques and vintage Persian rugs, Hurtwood was the archetypal Rockbroker Belt residence. Whitlock was in his element.

“We wrote ”I Looked Away”, “Anyday” and “Why Has Love Got To Be So Sad”. Meanwhile, the word keeps coming back about Radle and Gordon, tearin’ a hole in the world. One day we’re at the table and Eric takes a call. ‘Oh, hi George. Yeah. We can do that but we want to record a couple of things.’ He tells me ‘That was George.’ Harrison? Oh. Wow. Cool. Then Eric says ‘call Carl and Jim Keltner immediately!’ Oh, excellent!”

After knocking off a couple of none-too taxing sessions for Doris Troy and some production on an unreleased PP Arnold effort, Eric is itching to play properly. Keltner never makes it over so Jim Gordon deputises.

“For a while, we also had us ‘the Domino flat’ on 33 Thurloe Street, by South Kensington tube, round the corner from the Queen’s house. A real posh neighbourhood”, recalls Bobby.

George Harrison’s invitation now found the four amigos joining the star-studded cast that made the ex-Beatle’s triple album All Things Must Pass with producer Phil Spector. Whitlock played on every track bar one, including his first studio stab at the piano on “Beware Of Darkness”. He also sang back-ups on the title cut and “My Sweet Lord”. After June sessions for instrumental jams “Plug Me In” and “Thanks For The Pepperoni” the quartet knocked out two songs with Spector: “Tell The Truth” and “Roll It Over.”

Says Whitlock, “’Tell the Truth’ I wrote one night after we’d been up for days on one of our three-day marathons. I was sitting in Eric’s living room when this thing just hit me. I was a young man, gaining experience; that’s what I was thinking about.”

Briefly available as a single these songs can be seen as tentative first outings for Derek and The Dominos. The band made its live debut in the new guise at the Lyceum Ballroom a few days later where Harrison and Dave Mason joined them. The initial idea was to use Eric’s nickname, Derek or Del, while the American contingent would be The Dynamics. But joker Tony Ashton, of Ashton Gardner and Dyke, kyboshed that when he introduced them as Derek and the Dominos: the name stuck.

Tiring of his ‘Clapton is God’ moniker (most famously seen as graffiti on a corrugated fence next to the Angel tube station), Derek and the Dominos offered a stab at credibility. Clapton was in his element again, playing Delaney stuff like “Blues Power” and blues favourites “Crossroads” and “Spoonful” but now with a funkier edge than Cream’s progressive, solo flash style had dictated. The Dominos were tight-knit, travelling to small venues in Dunstable, Great Malvern and Torquay in Eric’s Mercedes, despite the fact he didn’t have a driver’s license.

While this incognito tour set the groundwork for what would become the lavish double, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, the boys combined feverish playing and manic excess on the road that summer, before decamping to Miami’s Criteria Studio in late August to record the album with Tom Dowd, the multi-track pioneer.

The Layla album was made in extraordinary, emotional circumstances. Obsessed with Harrison’s wife Pattie, Clapton wrote her a succession of open love letter songs including “Bell Bottom Blues” and “I Looked Away”. Since he found it hard to take his own lyrics seriously Eric’s main partner was Whitlock, an ingénue with bags of belief and a good memory.

“I was not credited for helping write a lot of that material. That’s part of the ego thing. Had I been credited on “Bell Bottom Blues”, that would have meant I had more songs on the Layla album than Eric.” That song, written in response to Boyd asking Clapton to bring her home a pair of bluebell bottoms from the US, predated the arrival of Allman and is remarkable for Clapton’s multi-track lead guitar, the percussive mix of snare and tabla and a romantic bluesy lyric that moves the form into the late-20th century.

Whitlock also played the infamous piano coda on “Layla,” the one that is always credited to Jim Gordon. “That’s wrong. He did play a few notes but he’s not a piano player. He plays so straight – everything is right on the money. They wanted me to give it some feel, so Jim and I recorded it separately and Tom Dowd mixed them together.” In any case, Whitlock believes that Rita Coolidge came up with the initial melody. Maybe we will never know.

Allman’s guitars mesh with Eric’s on eleven tracks, including a gorgeous reading of “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out”, Billy Myles’ “Have You Ever Loved a Woman” and Jimi Hendrix’s “Little Wing”.

Just as Jimi Hendrix had inspired him to form Cream, Duane Allman’s addition to the Layla sessions provided the catalyst for a lot of the music made in Miami but it was a mutual appreciation society. Allman described Eric as “a real fine cat, a man of the street and a gipsy. It was an honour to play on the Derek and the Dominos album with people of that magnitude, with that much brilliance and talent.” As ill-luck would have it both Hendrix and Allman would soon be dead.

Returning to England the band recommenced touring but the previously intimate venues were replaced by large auditoriums where the band took to wearing ‘Derek Is Eric’ badges in an effort to promote the album, which had got such a lukewarm response. In Concert, taken from two October 1970 dates at the Fillmore East, eventually documented the legendary US tour. We recommend the 40th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition and the 2013 issue, remastered with Blu-ray and Blu-ray audio: that’s the nuts. Vinyl fetishists can also seek out the singles, “Bell Bottom Blues”, the Spector-production “Tell The Truth”/”Roll It Over” (though beware of counterfeits; originals are rare), “Layla” and the awesome “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad”, a track that captures the essence of the Clapton-Whitlock partnership.

In retrospect, we can see the importance of the Layla album and still be puzzled as to its tepid reception, especially in the United Kingdom. After all, the Blind Faith LP topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic a year earlier. One reason may be that George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass was about to sweep the competition away on a wave of Hare Krishna transcendentalism, “My Sweet Lord” and all that. At their moment of implosion, The Beatles were bigger than ever. Of course, Clapton was sick of being tagged as God himself but his divine “Presence of The Lord” survived the transition from Blind Faith to the Dominos’ live set. It was 1970. Time for the rock church.

Words: Max Bell